Kampala - Uganda

[email protected]

Urgent and radical land use changes are needed to reconcile efforts to prevent dangerous climate change and tackle hunger, a major scientific report warned on Thursday.

Large-scale tree-planting and bioenergy production are important tools to limit global warming but could threaten food security, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

In late-running negotiations on how to summarise the latest science for policymakers, representatives of forest nations stressed that with sustainable management, these conflicts can be minimised.

“Land already in use could feed the world in a changing climate and provide biomass for renewable energy, but early, far-reaching action across several areas is required,” said Hans-Otto Pörtner, one of the leading IPCC scientists coordinating the report. “Also for the conservation and restoration of ecosystems and biodiversity.”

Left unchecked, global warming itself will damage ecosystems, eroding the capacity of land to support human life, the evidence shows.

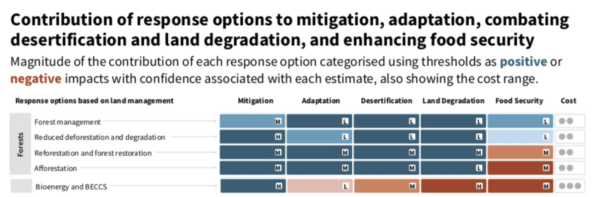

The special report on land use shines a light on the importance of afforestation and fuel crops to absorb carbon dioxide – and the associated risks of land degradation and increased desertification, which it said could have “potentially irreversible consequences”.

It covered controversial ways to limit global warming such as bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (Beccs): burning plants to generate energy and pumping the emissions underground.

“The report leaves no doubt about the devastating impacts that large-scale bioenergy, Beccs and afforestation with monocultures would have on water availability, biodiversity, food security, livelihoods, land degradation and desertification — a tsunami of threats that make large scale bioenergy and Beccs completely unacceptable and unworkable,” said Linda Schneider, senior programme officer in climate policy at the Heinrich Böll Foundation.

In one scenario, use of forestry and land to store carbon causes crop prices to soar 80% by 2050, translating into an extra 80 to 300 million people suffering from undernourishment.

This tension is however limited if trees are planted on land unsuitable for agriculture and used to prevent desertification and restore degraded soil. Small-scale planting of native species can also provide a safety net during times of food and income insecurity.

Another way to reduce competition for land is to crack down on illegal logging in protected areas and better manage existing forests.

Bioenergy, which can replace carbon-intensive fossil fuels, must be used judiciously to avoid tensions between feeding a growing population and tackling climate change, the report showed.

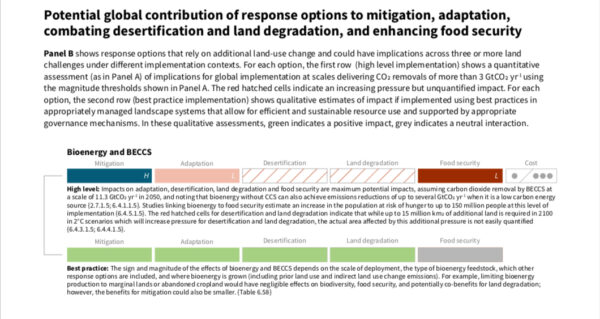

Extensive use of bioenergy – including with carbon capture and storage – puts an additional 150 million people at risk of hunger if used to reduce emissions by several gigatonnes of CO2 per year.

But limiting bioenergy crops to marginal lands could significantly reduce negative effects, potentially even enriching ecosystems and the soils in the process.

Those warnings come after national delegates and scientists spent a week in Geneva, Switzerland, debating what to include in the summary for policymakers (SPM), a 41-page document to guide governments.

Among the most contentious topics were passages detailing the downsides of large-scale bioenergy and forest plantations.

Led by Brazil, a group including the US, Canada, Sweden and the United Kingdom pushed back against a diagram in the draft that flagged several trade-offs in red. The final version separated out the contested elements, highlighting areas of scientific uncertainty and how best practice can bring dual benefits.

A draft of the IPCC land use report summary for policymakers raised several red flags around bioenergy

The final version emphasises areas of uncertainty and the benefits of following best practice

France and Germany, however, “stood firm in the face of attempts to water down high afforestation scenarios,” an observer told CHN.

The two delegations also championed “nature-based solutions” to restore natural landscapes such as mangroves and peatlands to soak up carbon emissions, according to three sources. The final version added several paragraphs on this theme, compared to the draft.

Jim Skea, a lead scientist on the IPCC report, told Climate Home News the final version introduced “a lot more nuance” about bioenergy.

“What was picked up from the previous draft was that the message about bioenergy was almost entirely negative because the figure assumed that it would be deployed at the scale that would remove at least 3Gt of CO2 annually… But we are not deploying bioenergy nearly at that scale at the moment,” he said.

“A number of countries quite rightly pointed out that if bioenergy was done properly – you chose the right crops, you regulated it properly, and did it at the right scale – that bioenergy could actually be beneficial.”

The more emissions could be reduced in the short term, the less bioenergy would be needed to meet climate goals, he added. “It depends on what we do on the other sectors, how difficult that trade-off will be.”

The report is part of a series of landmark publications by the IPCC aiming to arm governments with the best climate science ahead of 2020, a critical moment for UN climate negotiations. Next month will see the release of a report focused on oceans and the cryosphere – water in its solid state such as glaciers and ice sheets.